Hello Everyone!

I'd like to talk about the myth of "exploding crime rates" in our society and the consequences it carries. Recently, there was a lot of talk about a mother who

let her nine year old son ride the New York Subway and received an immense amount of criticism for it. In my experience women who do things like walk or take the bus alone when it's dark are often criticized for it, as has been the case since the 90's-and probably a lot longer. Some parents will not let their children walk to school for fear that they will be kidnapped or assaulted.

Of course, driving in a car carries its own share of risks and therefore the issue largely boils down to risk perception. Yet many people largely ignore those risks, but let the fear of crime dictate their actions. This could be because we are wired to fear interpersonal violence, more than accidents or it could be because of the conventional wisdom.

And to many if not most Americans, the conventional wisdom is something like this. During the 1950's nobody really worried much about their personal safety. People felt comfortable leaving their doors unlocked and letting young children run errands for their parents. But sometime after the 1960's, things changed. People started to live in fear. Children could no longer walk to school and women could no longer go outside alone at night. Crime rates exploded, and the safety that had once been taken for granted, became a distant memory. And this view tends to predominate on both the left and the right.

Of course, the left and right never did agree on the causes. According to most conservatives the rising crime rates could be blamed on decline in the "traditional" family, lack on "old fashioned" concepts of child discipline including spankings or even corporal punishment in schools, working mothers, gay and lesbians raising kids, and of course a justice system that is "soft on criminals". The solutions in this view include harsh punishments for criminals often including the death penalty, stricter discipline for young people often including measures such corporal punishment in schools or instituting a universal military draft to insure that most young men (and in some cases young women) go through boot camp, and the promotion of "traditional family values" which can include discouraging gays from raising kids, discouring divorce, and even discouraging mothers from working outside the home. Criminals if they could be reformed at all, would only improve under harsh often physical discipline, and possibly religion. Robert A. Heinlein a conservative science fiction writer described a 20th century that fell apart because parents did not spank their child "even as babies", in a lecture made by a teacher to his students in the book "Starship Troopers" in which the teacher told a student that it was impossible for any human to develop a conscience if they hadn't been spanked as babies.

And historically most liberals have taken the view that crime is the result of bad life circumstances and deprivation such as poverty, racism, discrimination, abusive family lives, and such. In this view the solutions include things such as greater social welfare programs, spending money on schools and education rather than police forces or jails, promotion of more job/educational opportunities for the less fortunate, the dismantlement of racism and other forms of social discrimination, more public education in areas such as parenting or non-spanking forms of child discipline, and such. Also some versions of this view have at times claimed many/most criminals could be reformed or rehabilitated variously with work programs, education, psychological therapy or counseling, and in some cases prayer.

Of course after two centuries of liberals sometimes viewing conservative ideas about crime as callous and lacking sympathy for those unfortunate enough to fall into lives of crime, while conservatives have been known to look upon liberal view as softheaded, naive, and rewarding bad behavior.

But what would happen if both of these views were wrong?

That crime in America has NOT consistently exploded since the end of 1959, and has in fact

dropped a great deal during the 90's, and has been dropping throughout

2009? That neither liberal, nor conservative, nor other theories about the causes of crime are terribly effective at explaining crime rates? Apparently that is our current reality.

One the whole comparing estimated and reported crime rates before the 1970's or so, to recorded rates in recent decades may be like comparing apples and oranges for several important reasons:

1) In the past police departments were often on the same page as city politicians in that they wanted to shoot for the lower estimates of local crime rates in order to make the community look good. In during the 70's police budgets became more influenced by perceived crime rates, and politicians found that exploiting fears of crime could be a way to get elected. This does not automatically mean that crimes were suppressed or fabricated. It simply means that estimates over large populations are not perfect, and that sometimes subjective choices are made over which one is the most reliable.

2) Often crimes were never reported in areas where the Mafia or KKK was powerful.

3) The installment of the 911 emergency number starting in 1968 (but it didn't reach some communities until the 80s) , along with the introduction of the National Crime Victimization Survey both added several crimes that were not reported to the police to the accepted crime statistics.

4) Some of the most dramatic increases in reported crimes in the 70's and early 80's involved rape, domestic violence, and incest. However starting in the late 60's the Second Wave feminist movement worked hard at encouraging women to report these crimes, to fight back, and to speak out against and the victim blaming/shaming attitudes that had prevailed for generations.

5) Modernization of statistical methods and the introduction of computers and more advanced communications.

6) Newer forensic methods made certain types of criminals (ei serial killers) easier to catch, and certain crimes easier to prove.

But whatever uncertainty might exist about actual crime rates in past decades, anyone who has seen the movie "

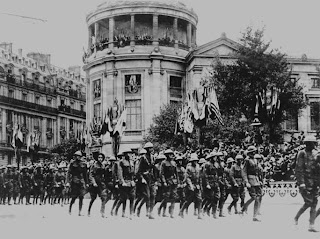

Changeling" or read books like "Huck Finn" or stories about "The Old West" with a critical mind, can figure out that the past wasn't necessarily a crime free Golden Age, and that police corruption is nothing new. While we shouldn't ever take serious crimes like murder lightly, it clearly does no good to think that violent crime is particularly rampant or perpetually on the increase. It is true that the United States as a whole has a very high murder rate for an industrial nation, however this murder rate only applies

to certain parts of the US, mostly in the Deep South. And that a recent decline in murder rates has shown

a good deal of variation in different places.

Another interesting aspect of crime rates is that by and large what both liberals and conservatives have traditionally believed about crime rates both appear to be wrong.

See previously posted article. In the 90's many people predicted that the decline in crime rates would reverse in the early 21st century because the number of young adults would increase. Yet with the coming of age of the hip hop generation, and the beginning of the Bush era,

that didn't quite pan out.

So it looks like the children of working mothers and high divorce, who didn't face a universal military draft, and grew up listening to rap and hip-hop didn't turn into the violent homicidal maniacs, wanton thieves, and lost drug addicts that many conservatives feared. At the same time traditional liberal expectations that economic deprivation is a factor in crime have no been supported by a trend towards increased crime rates during economic hard times. The controversial theory in Freakonomics, which could be welcome or condemned by factions on both the left and right albeit for somewhat different reasons, that legal abortion lowered crime rates also doesn't fit the facts. Not only did this effect not show up in other countries, as the article mentioned, but also the increasing difficulty obtaining an abortion starting in the late 80's and early 90's, along with the high teen pregnancy rate in the 80's, should have led to a marked increase in crimes committed by young people starting in the past few years rather the the current decreases, if it were true. Another hypothesis advanced by some thinkers such as Lt. Colonel Dave Grossman that better EMS services and medical advances are creating an artificially suppressed homicide rate, and masking true levels of violence is also highly doubtful given the decline in other types of violent crime as well. Ideas suggesting that the levels of gun ownership cause or decrease crime, are generally not back up by any strong evidence. The notion that cultural attitudes are an influence could explain regional differences but not fluctuations in the national crime rate. Some might suggest that various political cycles or the "spirit of the times" could influence crime rates, but I've yet to see a clear working hypothesis that can be shown to fit the actual facts.

One of the things this situation reveals is that for over 200 years Western society has debated the root causes of crime in a highly politicized framework with surprisingly little basis in hypothesis testing, and beneath it all tantalizingly few clear working hypothesis that seem to explain much about crime rates. As an college student in the 90's, I was very strongly attracted to Ralph Nader's somewhat beyond left and right view, that contrary to popular opinion the poor did not commit the majority of crimes in America, and that the media failed to focus on corporate crime, white collar crime, and middle class drug abuse the way it did on crimes committed mostly by the poor. In the early years after 9/11, although no supporter of the Bush administration or its wars, I considered the link between the attacks on America and radical Islamic fundamentalism, to issues like world poverty to be questionable and the relationship to misguided US foreign policy to be at the very least less simplistic than was usually portrayed. In both cases, I found myself to be in the minority: assumed to be conservative by many leftists and seen as an iconoclast or a fool by nearly all conservatives.

Of course, in those days I was younger and relied mostly on facts and figures for this position, although they were far from uninfluenced by my own experiences. However, in more recent years, I've come to depend more on my own experience in life: Namely that basic decency among most people is much more resilient than liberal theories about deprivation and bad circumstances, conservative theories about the decline in values and lack of discipline, or iconoclastic Naderite views blaming the decline of civic values and the triumph of corporate selfishness, would have us believe. And the presence of malice and wickedness in some people is much more mysterious, than most of the explanations I've seen can do any real justice to.

But either way, I can see four possibilities with regard to explanations for crime rates:

1) That people will continue to debate the liberal/conservative frame of crime that has been in place since at least the early 19th century, even though it has little real value.

2) That a new set of theories with limited real world value will end up being hotly debated and politicized for some time-perhaps another 200 years!

3) That some new unforeseen model will arise that actually works, and if that happens, I doubt it will support either right or left wing politics in any neat and tidy way

But one thing is fairly clear. The realities of crime do not seem to fit the historical partisan framework. And any politician who uses fear of crime to get elected is operating on false premises. Improving job opportunities for the poor and funding schools are worthy goals, but not effective ways of reducing crime. Perhaps a better argument for creating opportunities for the poor and better school systems, is simply that they would benefit society and large numbers of people, most of whom were never likely to become violent criminals.

Equally important is bringing the public's perception of crime closer to the reality. Because a skewed perception has contributed to the public's reluctance to use public transit, abandonment of city center and urban sprawls, overprotection and lack of exercise among children, increased racial prejudice, the perception that women must avoid traveling alone and other social problems.

But in looking at the culture, I see some signs that the public might be more ready to engage in sophisticated discussions of crime than was the case in the past. TV shows such as "Cold Case" and "Law and Order" rarely portray criminals as sympathetic figures, but they tend to put the crimes in a historical or political context that reflects a largely liberal outlook. Newer crime films include portraits such as "Zodiac" with it's in depth character study of the people who were connected to the investigation of the Zodiac murders and how it affected their lives over two decades. And "Changeling" with deals very well with issues such as serial killers, a morally ambiguous portrait of the death penalty, police corruption, a feminist view of abuse of power, and a realist portrayal of children confronted with violence. These movies and others already deal with more multi-dimensional realities than the historical liberal/conservative dichotomies .

I'm confidence that our political discourse overdue for the same thing.

Say Goodnight Readers!